This is the sequel to the sleuthing for the truth article about Brink. First, I should say that it’s a little unfair to compare Brink to Left 4 Dead 2. Brink is essentially a competitive game, whereas Left 4 Dead 2 is co-operative – even in Versus mode. Co-op games offer more time and space for in-game storytelling than competitive ones, because competitive shooters like Team Fortress 2, Counterstrike, or Brink tend to lead to manic, twitch gaming. The best you can hope for with such limited time and attention is some well-placed one-liners. In a co-op game, the experience is more managed, with lows, highs, and potential story moments – similar to single-player.

As we know, Brink chose to circumvent its story difficulties by placing mini-cutscenes before and after levels. Thus, they delivered story outside of the core competitive experience. In Left 4 Dead 2, Valve follows its tradition of keeping game narrative in-engine, and almost all of it playable. Missions may begin with in-game dialogue between Survivors to set the scene, but it is short, and does not interfere with immediate play. Missions may end with a short ‘cutscene’, but it’s really more of a scripted event within the game engine – a bridge exploding, or a helicopter taking off.

Both sides of the narrative divide

The Left 4 Dead games are rather self-contradictory in their approaches to story. They embed some story completely within the game experience – in the environments, in procedurally-cued dialogue during gameplay – and then other story is delivered not only out of gameplay, but out of the game entirely. Valve has released online comic strips that add a great deal of context to the game’s canon, but are nowhere near embedded in the core narrative experience of the game – they are not even accessible from the game’s menu, and aren’t part of the download.

What Valve has recognised is that not only is full-on story hard to do in any sort of multiplayer game, but more importantly, the majority of players do not want to have too story-centric an experience on maps they will be playing again and again. Thus, dialogue is short and snappy, establishing context, location and objective as quickly as possible, and sweetening it with a little humour.

Left 4 Dead also pitches each mission as if it were a horror movie, complete with its own movie poster and tagline, and ending with ‘credits’ that list your achievements and statistics. As well as being a cool gimmick in suitable company with the game’s “film grain” setting, this also lets Valve encapsulate each map, whether it be Hard Rain or The Parish, as a stand-alone experience with its own internal scenario. Sure enough, in each map the same basic premise will be true – the Survivors struggle to make their way to safety through the plentiful hazards of the zombie apocalypse.

This notion that each level is a contained experience gives Valve the handy excuse that any lapses of continuity between missions, or confusion about it, can be ignored, because the level itself will be fun to play regardless. But this “stand-alone” approach to missions is also one of the game’s weaknesses.

Too much work

This post was delayed. The reason was that, the further I dug into Left 4 Dead 2’s story, the more I saw that there were links tenuously being made between levels, but their abstraction and lack of emphasis made it difficult to put the pieces together. Rather than determining the putative “order” of the missions through simple analysis of an overarching plot or trajectory, I also had to engage in a process of deduction where I considered what missions were clearly linked, and therefore what other links could not exist, until I arrived at the only sensible ordering.

Of course, if I’d been smart, I would have looked at the fan-maintained Left 4 Dead wiki at the start. Instead, I played through all the missions of the game: if you can’t find out the story by playing the game, what’s the point?

But your typical player is not going to go to a wiki to find out more about the story. He will (if you’re lucky) play all the way through the game, and that will be the extent of his exposure. If he isn’t convinced, or doesn’t get it, one of the things he won’t be telling his friends is how cool the story is.

Having said that…

…the links are there. Because some of the locations – like Rayford – exist only in the Left 4 Dead world, you can’t simply chart the progress of the Survivors on Google Maps. So the best way to figure out what happened when is to see how the Survivors enter a place and how they leave. Thus, the order:

The Survivors start by just missing an evacuation chopper on a high-rise. This is near the beginning of the outbreak of the ‘green flu’ – the Infection. We know this is the first map for sure, because the survivors introduce themselves during an elevator ride. They finish the level by escaping from Liberty Mall, refuelling and stealing stock car racer Jimmy Gibbs Jnr’s showcase vehicle.

The Passing

They arrive at a bridge, which needs to be let down if they are to cross it with the car. They encounter the Survivors from Left 4 Dead 1, minus Bill, who has made the ultimate sacrifice. If they will go under the river and power up a generator from the other side, the bridge can be lowered for them to cross with the car. They do so, presumably enabling the original Survivors to make their final getaway using the yacht they originally sought in The Sacrifice. They drive across the bridge.

Dark Carnival

They are forced to abandon Jimmy Gibbs’s car due to a massive pileup on the freeway. They make their way to Whispering Oaks fairground and start the pyrotechnics in a massive concert arena to attract attention. They flee the horde in a rescue chopper.

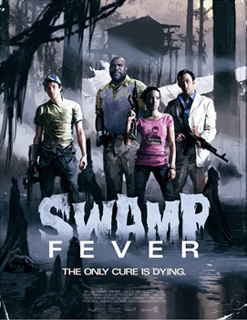

Swamp Fever

The connection between Carnival and Swamp fever is sketchy. Swamp starts with Ellis berating Nick for shooting “the pilot” after he turned into a zombie, causing them to crash. We can only assume this is the chopper pilot from Carnival, although The Parish also ends with a helicopter escape. Swamp Fever’s narrative is less focused than the other missions. There’s a swamp, there are some walkways, and Coach mentions a ‘tour’, but it’s unclear if he’s being ironic. Beyond ‘surviving’ there is no clear objective driving the survivors’ movements, until the finale when they call a fishing boat for rescue from the Plantation House.

Hard Rain

The boat’s captain, a Cajun named Virgil, drops them off to pick up diesel for his boat. They make a circuit through town, encountering a massive storm, and return to the boat with the gas.

The Parish

The Survivors are finally in New Orleans, which seems to have been their goal based on comments made in The Passing and also scrawled notes within the safe rooms throughout. Virgil drops them off with his boat, saying that they can ‘make it to the bridge from here’. But it’s not clear why they would want to go to the bridge in particular. Nevertheless, they do, and atop the bridge is a dead CEDA agent with a working radio. Military jets continue bombing the city from above as the Survivors cross the bridge (which then explodes) and make their way to another rescue chopper.

Cold Stream

This is a community-created map that will be released by Valve. It’s currently in beta, but is not intended to exist within the official story canon.

When it’s laid out like that, it all seems fairly straightforward. But it’s hard to figure out because none of those links are explicitly made in the game – the game menu doesn’t even list the maps in that order, and neither does it suggest that Dead Center is the first map in the game (though it is, at least, the first in the list).

The smart stuff

So the biggest problem for Left 4 Dead’s narrative is the obscurity and difficulty of tracking it down. Having said that, I believe if you treat gamers like persistent, intelligent people and give them a puzzle, they tend to figure this stuff out, and sometimes get more out of the process than if you try to cover all the bases in an obvious way.

And L4D2 does deliver narrative in a bunch of smart, if obscure ways. The characters introducing themselves during the elevator ride in Dead Center happens so quickly you could miss it, but it tells us where in the story we are. Likewise, in the first two parts of that campaign, you’ll find that the Infection is at such an early stage that the Survivors are encountering Special Infected they haven’t even named yet. Thus, Rochelle says ‘What in the hell is that?’ upon seeing a Tank. They’ll call out, ‘Jumping zombie!’ instead of Hunter, ‘One-arm!’ and ‘Overalls!’ instead of Charger, and ‘Fat guy!’ for Boomer. By the end of Dead Center’s fourth and fifth chapters, they have named all the Special Infected and always use the correct names.

You also get a lot of background information about CEDA, the infection and the state of nearby towns via the scrawled messages in the Safe Rooms throughout the game. These also provide incidental, amusing, and frequently misspelled insights into human nature.

The ugly stuff

At the same time that Valve are doing all this clever work with telling the story through the environments and incidental dialogue, they make a strangely elementary mistake in not better tracking what audio is heard, when. It’s quite possible for procedurally-generated, story-relevant audio to be cued for more than one character at the same time, so you get three Survivors suddenly all talking about what they should be doing over the top of one another. It’s also quite possible to reload your gun while your character is saying something about why you’re going where, and for him to interrupt himself, killing that audio, in order to yell, “Reloading!” – certainly a useful gameplay bark, but not one we should be overly concerned about missing, especially since it doesn’t even cue every time.

As might be expected, there is still important work to be done in improving procedurally-controlled story mechanisms. One of the more interesting parts of working on Driver: San Francisco was trying to design procedural audio mechanics that would result in the most rewarding and most script-appropriate gameplay speech during the course of ‘free drive’, when the script, passenger and car in question could be any one of hundreds. Considering what should be interrupted, when, is no easy matter – especially when your knowledge about what has gone before is so limited. By the time the game shipped, the number of times and ways in which speech could interrupt itself was greatly reduced – and all beneficially, I believe.

Likewise, it’s rumoured that Frontier Games’s The Outsider was/is supposed to be ground-breaking in its approach to larger-scale procedural storytelling, where choices would substantially branch the main structure and story of the game. The fact that the game has been semi-cancelled is a telling indictment of the technical and artistic difficulties in doing this right – or doing it at all.

The future

It should come as no surprise that neither Splash Damage nor even Valve has fully cracked the telling of story through multiplayer games. Both have taken very different, but equally bold approaches to the problem. As with everything in games development, a surprising number of restrictions upon what appears on the surface to be a ‘writing problem’ are actually technical. As Valve promises that all its future games will have a multiplayer component, it will be fascinating to see how these methods develop.